|

|

|

|

Image

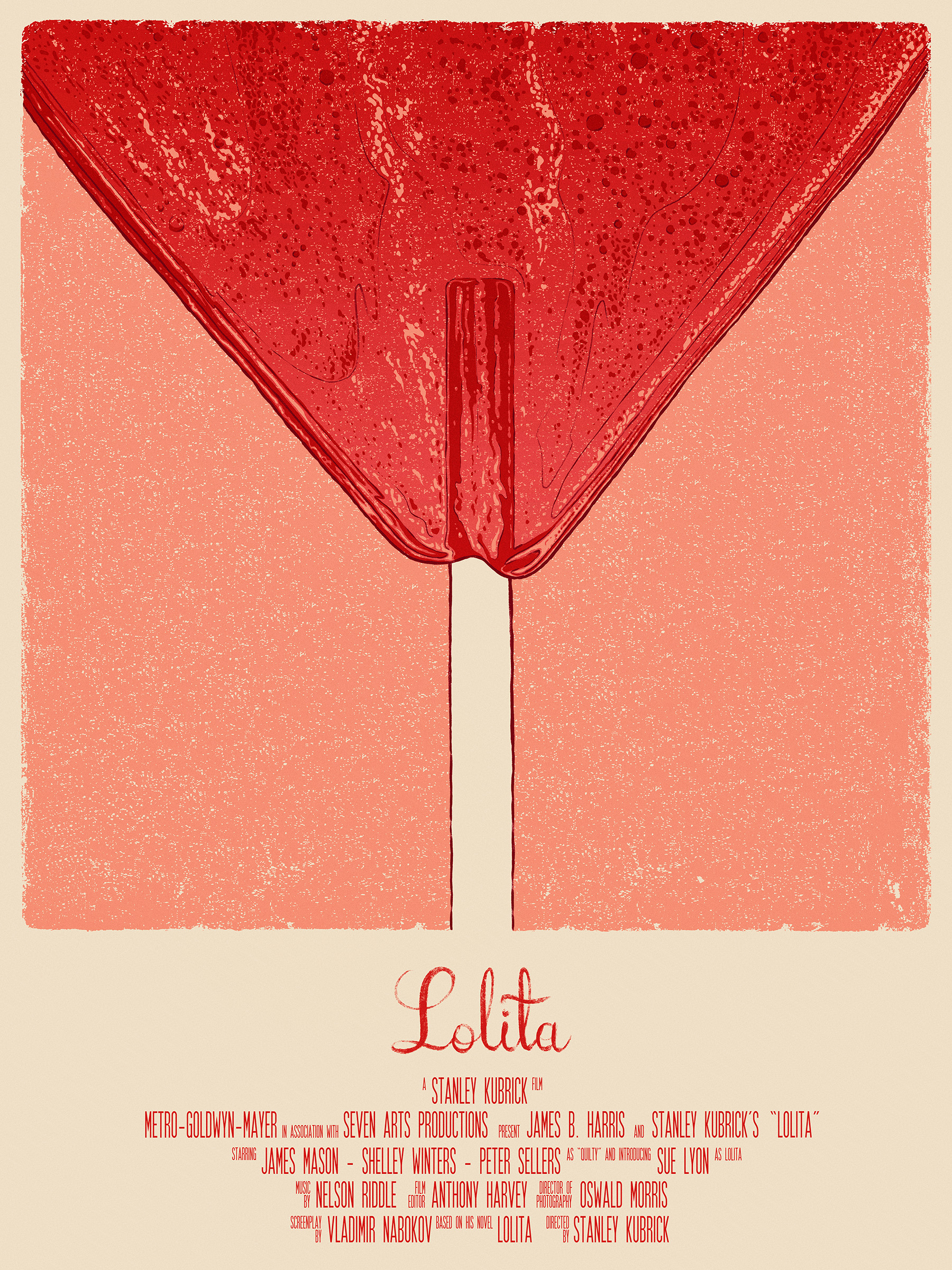

American filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s eponymous adaptation of Lolita (1955), Russian writer, Vladimir Nabokov’s classic novel, famous for its depiction of an illicit relationship between a middle-aged man, a European-bred belletrist specializing in French prosody, who had traveled to the U.S. to take on the Professorship of French Literature at Beardsley College, Humbert Humbert, and the teenage daughter, Dolores Haze, affectionately tagged as Lolita, of his landlady turned wife, Charlotte Haze-Humbert, has been a cultural touchstone for such aforementioned liaisons since its summer release in 1962.

Even so, what the film explores is not the mind of a depraved pedophile as its premise of an adult male renting a room in the home of a forlorn widow whose little girl he has designs on—and readings of the book—might suggest, but, rather, an infantilized, tragic hero, wrestling with the downside of the human condition, possessed by a universal passion.

A sophisticated plot poses questions not only to the protagonist, answered in the climax, or moment of discovery occurring in its anagnorisis, but the audience itself, building suspense, creating an uncertainty in outcome that’s dispensed with in a catharsis, as the full relationships of events takes shape, of which one example is the opening scene in James Baldwin’s brilliant, metaphorical Giovanni’s Room, a novel, wherein to whom the space belongs, the homosexual paramour of the narrator, David, is said to be executed by beheading for a crime not stated, or the deathbed utterance of publisher Charles Foster Kane, “Rosebud,” in Oscar Best Picture Winner, Citizen Kane; perhaps, the best cinematic use of such a literary device, in medias res, or nonlinear narrative.

Similarly, Lolita commences with the domestic murder of Claire Quilty, a lonesome, mystery man, surrounded by the remnants of a certain party, hungover, wearing a bath robe, at the leather-glove-clad hands of Humbert Humbert, by way of a .38 revolver, a scene that was moved forward from the film’s end, as it is in the book, as well as Nabokov’s screenplay—one of many changes too numerous to discuss here, and not necessarily relevant to the criticism of this piece—by Director Kubrick, significant in that it draws the audience’s attention away from the seduction of an underage girl, turning the controversial composition into not just a work of moral intrigue, but of a reverse-murder mystery, which has the effect of sanitization, cleansing the piece of a bit of its inherent taboo due to its corrupt subject-matter.

The first occurrence of any affection between the professor and his object of preoccupation comes when Humbert, pinched between his two roommates, at a drive-in movie theater, has his hand gripped by Darlene, who’d reflexively reached down, responding to a harrowing scene, which also saw the elder Haze correspondingly embrace the Ph.D.; both ladies, however, relinquish their grasps, but not before the once-married, widow, approaching middle-age, briefly, notes her only child’s atop her tenant’s—a site she’d surely revisit, later, upon learning of her soon-to-be husband’s infatuation, flipping through his confessional diary, and soul-wrenching disdain for her.

“You’ll never see that miserable, little brat again,” she told the professor, in wake of the discovery, though she might as well have been talking about herself, as she was soon hit by a car, running in the street, during a rain storm, in hysterics from a broken heart, and, simultaneously, solving a dilemma for her husband, namely, how he’d persuade Charlotte to disregard what she had read as fiction—part of a novel he’d begun working on.

Free from the prying eyes of his deceased wife, Humbert, having collected Lolita from Camp Climax, a pun, where her mother had sent her in the beginning of the summer to give herself an empty home in the hopes of forming a relationship with the professor, an undertaking she immediately achieved through the confessing of her inclination to marry him, in a letter the European responded to elatedly, holding the belief he’d see Darlene again and not have to leave, at the summer’s end, when he was to depart, with giddy and mocking laughter, at last, completed his pursuit of Ms. Haze—who’d learned “many games,” but one that was “especially good,” from a camp staffer, by the name of Charlie—staying the night at a hotel, where Dr. Humbert would engage the man he’d eventually murder groveling in his bathrobe.

Playing the role of eiron, an archetypal character in Greek drama, the villain in tragedy, whose passions aren’t ruling, unlike the alazon, the hero, Prof. Humbert’s, Quilty, posing as a police officer, part of a contingent of law enforcement in town for a retreat, questions the European about his room, while outside the hotel, on its porch, among other things to do with his “daughter,” as she’s described by her stepfather, displaying a thinly-veiled skepticism of his nocturnal interlocutor, the Ph.D., and the dissembler’s own fascination with Haze, as the weary sophisticate, dutifully, answers his enquiries, waiting on a collapsing bed—that would in the end arrive, to his disappointment, denying him an excuse to not sleep on his own.

The forbidden nature of Humbert and Lolita’s fraternity, which is explicitly sexual in the book, is subtly hinted at, instead, with censor-acceptable displays of intimacy, like Darlene’s caressing of the professor’s forehead, kneeling before him recumbent, on a cot, ahead of her bed, in their hotel room, and the painting of her nails, atop hers in Beardsley, an interaction in which Ms. Haze, noticeably, eschews making eye contact with her stepfather as she attempts to lie, ostensibly at the behest of Mr. Kubrick, who would’ve instructed Sue Lyon, the actress playing Darlene, not to, part of an appreciable pattern throughout the film of deceit, following their initial jaunt alone together minus Mrs. Haze-Humbert, conveying a youthful indifference, contrasted with the European’s fiendish, interrogatory queries of her recent after-school activities.

Escaping the suspicions of their chattering neighbors, with regards to their clandestine communion, as well as internal problems, brought to their attention, in part, by boisterous, shouting matches, within their own entanglement, the pair set out on a road trip across the country, a calamity for the professor, in that, having been tailed by a mysterious automobile, Lolita develops an illness, requiring a hospital stay that ends in her being checked out by a man who’s described to a disconsolate Humbert as her uncle by officials, leaving him with not a single lead with which to track her down, and having to be restrained by orderlies as he attempts to search for her himself in what had been her room.

Darlene writes her stepfather three years later in a letter informing him details of her life that would ruin the film's ending and, therefore, not be divulged here, but which prompt him to show up at her doorstep, shortly thereafter, bearing thirteen-thousand dollars, which he tells her are the proceeds, partly, from the sale of where they had initially met, her mother’s New Hampshire home, before traveling to Beardsley in Ohio, presumably having sold it just within the elapsing week or so since he’d received her missive, finally severing himself from the young woman with the relinquishment of the one-remaining item binding them together.

Desperately, during this, their final exchange, Humbert beseeches Lolita to return with him, eliciting bewilderment, and a devastating refusal that brings him to tears, prompting Haze to apologize for cheating, eventually making the admission he had not been the one man she’d “ever really been crazy about,” reifying his love of that unfortunate type, unrequited.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION